Abstract

The endangered eastern spotted skunk Spilogale putorius is an understudied member of the skunk family (Mephitidae) who have shown a significant decrease in population and range since the mid-20th century. Multiple knowledge gaps exist about this species which causes difficulties when organizing a conservation plan. In this study, I used data on observations of eastern spotted skunks and their possible predators and competitors from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, as well as data on habitat type for each occurrence using the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Land Cover Database. These were used to investigate 1) a competitive relationship between members of the skunk family and other generalist omnivores 2) the significance of a predator’s presence on the abundance of eastern spotted skunks, and 3) whether some habitat types are preferred by the eastern spotted skunk. 494 total 5 km$^2$ paired plots were created from these data sets and were used to determine the community and habitat composition of areas with and without eastern spotted skunks. Plots showed no significant difference in community and habitat composition, but plots with red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis) had a significantly lower abundance of eastern spotted skunks. These results show evidence for a predator-prey relationship between red-tailed hawks and eastern spotted skunks; however, additional research is warranted for community and habitat composition at a finer spatial scale.

Introduction

The eastern spotted skunk (Spilogale putorius) is a generalist omnivore in the skunk family (Mephitidae) and was often harvested in the fur trade during the early-20th century, with around 100,000 animals harvested per year1. Despite being once abundant in the midwestern and southeastern United States1, it is classified now as a vulnerable species by the IUCN, who estimate that its range has declined by at least 90% since the 1950s2. Being an under-researched species, multiple knowledge gaps exist which make it difficult to determine the factors attributing to their decline and design a conservation plan3.

The question remains of what could be driving the decline of eastern spotted skunks. Some possible answers to this include habitat changes, such as the reduction in corn production over time. In areas where corn plantings were reduced, it has been observed that the spotted skunk had to diversify its diet due to the decline of a primary food source4. Striped skunks (Mephitis mephitis), a closely related species to the eastern spotted skunk, that co-occurred in these same areas did not show any evidence of diversifying their diets despite sharing the same source of food, and it is suggested that this is due to the striped skunk being potentially competitively dominant and having lower metabolic demands4. The eastern spotted skunk is also a prey item for multiple predators such as great horned owls (Bubo virginianus), bobcats (Lynx rufus), and dogs (Canis lupus familiaris)5, and it is likely predation is a factor contributing to their decline and made more significant due to habitat loss and competition. For any conservation effort, it would be necessary to determine the causes of the species decline in order to address and reverse it.

Prior to this study, an analysis of communities with eastern spotted skunks with respect to their habitat types and colocation with other species at this scale has not been produced. To address this and investigate community-based factors for the decline of the eastern spotted skunk, I used observational and land cover data to test the following three hypotheses:

- Presence of a dominant competitor will result in the decreased abundance of the less successful competitor. In this case, the eastern spotted skunk would likely be the least successful competitor due to its small size compared to other omnivores, with an average body mass of 350 g6. I predict that the striped skunk will have a strong competitive relationship with the spotted skunk due to having overlapping niches as a result of their similar diets and behaviors67. As a result, locations with an abundance of striped skunks will have a lower abundance of spotted skunks.

- Predation will limit the abundance of a prey species. I predict that areas with high predator abundance will have a lower abundance of eastern spotted skunks.

- Species will select habitats that provide the best fitness. Certain habitats may be more preferable to the eastern spotted skunk than others. For example, areas with ground cover may improve the skunk’s ability to hide from predators such as owls6, and some areas may provide more food. Because of this, I predict that the eastern spotted skunk will be most abundant in agricultural habitats such as corn farms as they would provide both food and ground cover4.

Methods

Data on eastern spotted skunk and competitor occurrences was acquired from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility8. This dataset contained occurrences of predator species such as red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis), great horned owls (Bubo virginianus), red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), swift foxes (Vulpes velox), coyotes (Canis latrans), domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris), bobcats (Lynx rufus), and potential competitors like Virginia opossums (Didelphis virginiana), common raccoons (Procyon lotor), eastern spotted skunks (Spilogale putorius), and striped skunks (Mephitis mephitis). The dataset was limited to occurrences in the contiguous United States of America from the years 2000 to 2023, and was downloaded on November 23, 20248.

Annual land cover data was acquired from the National Land Cover Database provided by the U.S. Geological Survey9. This dataset contained image files of land cover throughout the continental United States, and each pixel in the image was a 900 m$^2$ square containing a land cover value representing the habitat type.

Occurrence data was processed by removing any occurrences that did not have any location data, as this would prevent it from being plotted on the land cover map. Only information like the GBIF identification number, location, date of observation, and observed species were kept in the processed dataset. The land cover value for each occurrence was computed using its location and the land cover dataset for that year to determine the habitat where the specimen was found. Land cover values were then reduced to six main habitats: wetland, agriculture, developed, forest, shrub, and grassland. This was done to group similar habitats as well as to remove land cover types that could not support these species, such as barren habitats with little vegetation.

The land cover and occurrence datasets were combined to produce a group of paired plots that could be analyzed further. Paired plots were constructed first by determining the species abundance and composition around each occurrence of eastern spotted skunk. Due to being a threatened species, the location data was obscured for each occurrence of eastern spotted skunk, such that any point within a 0.2 degree difference of its location had an equal probability of containing the eastern spotted skunk. The first plot was constructed by taking a random point within that range and making a 5 km$^2$ square around it, using a plot of this size to increase the likelihood of finding another species in the plot. The land cover percentages and abundances of each species was calculated, and the same was done to the second plot constructed adjacent to or 500 m outside the range of the first to produce a set of paired plots.

The relationships between eastern spotted skunk abundance, land cover type, and abundances of other species was analyzed with ANOVA using R (version 4.4.2). I ran two model selection exercises to determine which combinations of predators and competitors and which combinations of land cover types best explained the abundance of eastern spotted skunks. Of these variables, red-tailed hawk abundance and agricultural land cover percentage explained the abundance of eastern spotted skunks the most. These variables, including striped skunk abundance to test the dominant competitor hypothesis, were used in a set of linear regressions to relate the abundance of eastern spotted skunk to each variable. In the ANOVA analyses, the eastern spotted skunk abundance was used as the response variable with either striped skunk abundance, red-tailed hawk abundance, or agricultural land cover percentage as the explanatory variables. Similarity of habitats containing eastern spotted skunks with respect to habitat and community composition was analyzed using an ANOSIM with R’s vegan package (version 2.6-8) and the Bray-Curtis metric (9999 permutations).

Results

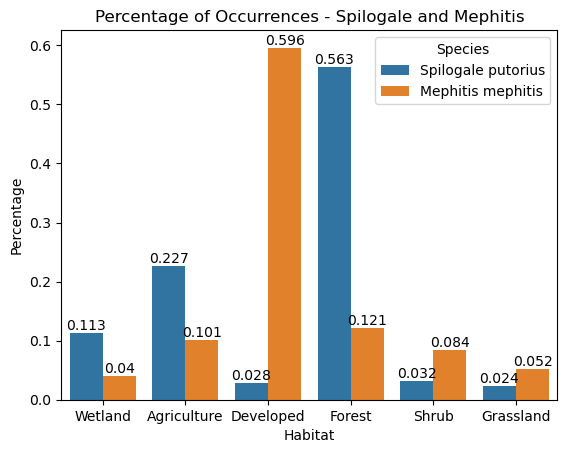

When analyzing the observational data set, it was found that there was a greater percentage of occurrences of striped skunks in developed habitats than spotted skunks. Observations of spotted skunks most often occurred in forest habitats (Figure 1).

After locating and plotting 247 occurrences of eastern spotted skunks, 494 total 5 km$^2$ plots were produced containing community composition and percentages of each habitat present for each plot. Plots were classified as having eastern spotted skunks if they contained any number of eastern spotted skunks.

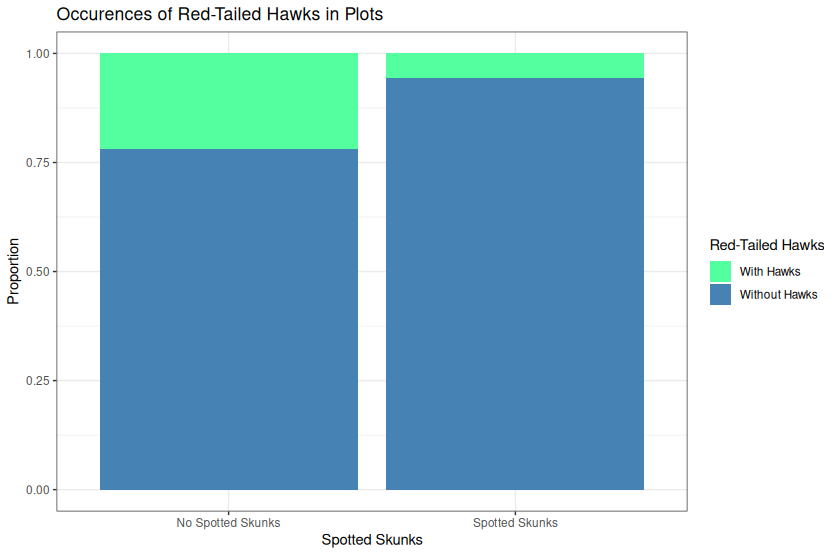

Results from the ANOVA using the abundance of eastern spotted skunks as the response variable and agricultural habitat percentage as the explanatory variable did not show a significant difference (estimate=0.00107, t=1.274, df=492, P=0.203). As well, there was a negative relationship but no significant difference between striped skunk abundance and eastern spotted skunk abundance (estimate=-0.51829, t=-1.441, df=492, P=0.15). Spotted skunk abundance showed a significant negative relationship with red-tailed hawk abundance (estimate=-0.02344, t=-3.092, df=492, P=0.0021). Eastern spotted skunks were more likely to be found in plots where no red-tailed hawks were present (Figure 2).

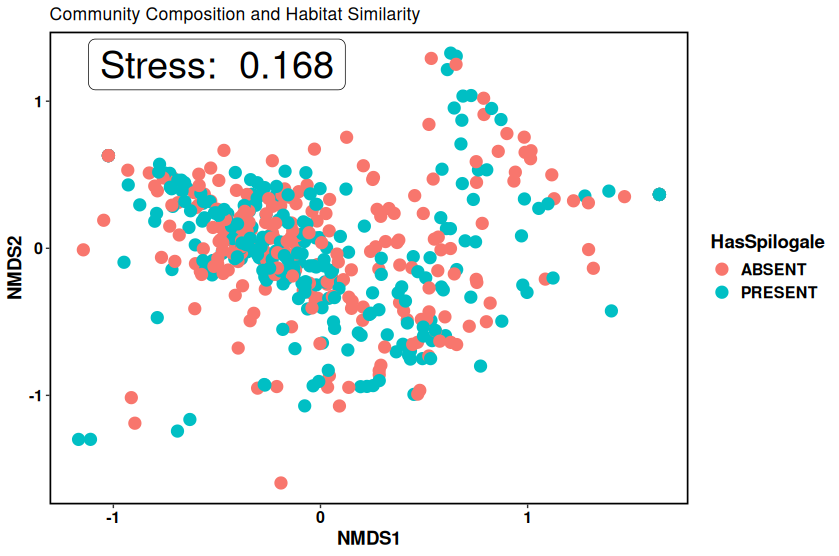

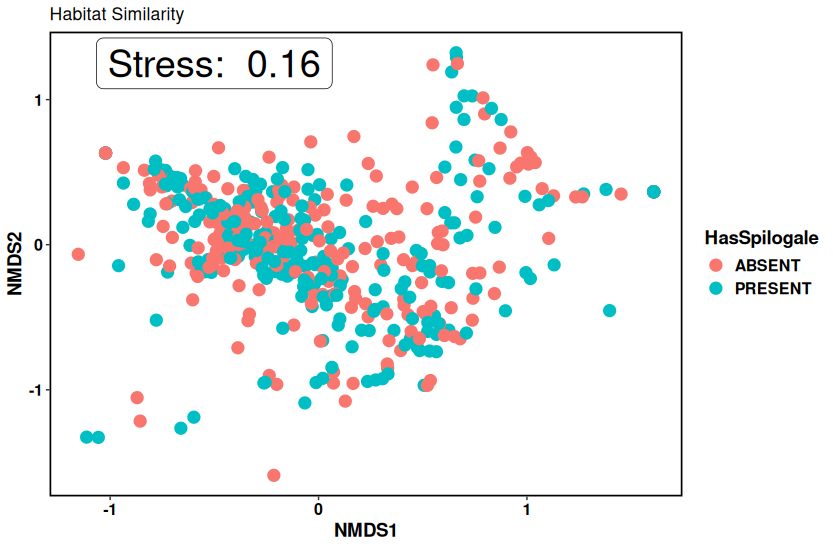

With respect to community and habitat composition (Figure 3), plots were grouped randomly and there was no significant difference between plots with and without eastern spotted skunks (R=-0.001, P=0.570). Similarly, analyzing just the habitats of each plot (Figure 4) showed no significant difference between plots with and without eastern spotted skunks (R=-0.002, P=0.696).

Figure 1: Percentage of habitats where Spilogale putorius and Mephitis mephitis were observed

Figure 1: Percentage of habitats where Spilogale putorius and Mephitis mephitis were observed

Figure 3: Proportion of plots where either red-tailed hawks and spotted skunks were absent or present

Figure 3: Proportion of plots where either red-tailed hawks and spotted skunks were absent or present

Figure 3: NMDS of plots with and without eastern spotted skunks with respect to community and habitat composition

Figure 3: NMDS of plots with and without eastern spotted skunks with respect to community and habitat composition

Figure 4: NMDS of plots with and without eastern spotted skunks with respect to habitat composition

Figure 4: NMDS of plots with and without eastern spotted skunks with respect to habitat composition

Discussion

Based on the results from the ANOVA analyses, there was evidence to suggest that the hypothesis of predation limiting the abundance of a prey species, such as the eastern spotted skunk, is supported, and it is shown that areas with high numbers of red-tailed hawks have lower abundances of eastern spotted skunks. However, there was no evidence to support the hypotheses that competition is limiting eastern spotted skunk abundance or that eastern spotted skunks select a specific habitat. Striped skunk abundance did not have a significant relationship with eastern spotted skunk abundance as predicted. As well, eastern spotted skunks were not shown to be more abundant in agricultural locations or to prefer a specific habitat, as habitat composition with and without spotted skunks were not shown to be dissimilar.

The results from the ANOVA relating eastern spotted skunk abundance and red-tailed hawk abundance is consistent with current research, as avian predators are suggested to be the main predators of spotted skunks (Spilogale spp.)10. Research also suggests that eastern spotted skunks will prefer habitats with foliage cover to prevent avian predation11 such as dry prairie shrub lands in Florida where eastern spotted skunk density is high12, however this was not supported by the results with respect to habitat composition. One possible cause for the ANOSIM analyses on habitat composition showing no dissimilarity between plots with and without spotted skunks would be the size of the plots, as they are so large that it is difficult to determine which specific habitat the eastern spotted skunk would be found in the most.

A limitation in observational datasets is that occurrences will be more likely to be recorded in locations where people are, such as in developed habitats, and when the species is visible. The size of the eastern spotted skunk and its preference for ground cover would make it more difficult to observe compared to the striped skunk. As well, the number of observations for eastern spotted skunks were greater in forest habitats while observations of striped skunk were greater in developed habitats. For these reasons, plots with eastern spotted skunks would likely be found in areas where there were none or few striped skunks, which could be responsible for the lack of a significant relationship being observed between the two species.

Current research suggests that great horned owls are one of the eastern spotted skunk’s main predators6, and from these results it is possible that the red-tailed hawk, another bird of prey, serves a similar role as an effective avian predator. Further research on the red-tailed hawk’s hunting strategies may offer more information about this predator and prey relationship.

Currently, there are multiple knowledge gaps and very little research on the eastern spotted skunk and its ecological interactions13. Future work should look to investigate survivability in specific, local habitats with respect to the composition of the community. Because the eastern spotted skunk has higher density and abundance in some areas than others, determining the factors responsible for this may be generalizable to other locations and would benefit conservation efforts. Long term field observations may offer more detailed measurements of eastern spotted skunk abundance along with the abundances of other species in the area.

Files, Datasets, and Processing

Effects of Competitor Presence and Habitat Type on Eastern Spotted Skunk Abundance PDF

References

-

Matthew Gompper, E., and H. Mundy Hackett. “The long-term, range-wide decline of a once common carnivore: the eastern spotted skunk (Spilogale putorius)”. Animal Conservation Forum. Cambridge University Press, 2005, pp. 195-201. ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Jachowski, David, and Matthew Gompper. “The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016”. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, Oct. 2015. https://doi.org/s. ↩︎

-

Eastern Spotted Skunk Cooperative Study Group. Eastern Spotted Skunk Conservation Plan. 2020. easternspottedskunk.weebly.com. ↩︎

-

Cheeseman, Amanda E., Brian P. Tanis, and Elmer J. Finck. “Quantifying temporal variation in dietary niche to reveal drivers of past population declines”. Functional Ecology, vol. 35, no. 4, 2021, pp. 930-41. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Harris, Stephen N., Jordan B. Holmes, and David S. Jachowski. “First Record of Consumption of a Spilogale putorius (Eastern Spotted Skunk) by an Alligator mississippiensis (American Alligator)”. Southeastern Naturalist, vol. 18, no. 2, 2019, N10-N15. ↩︎

-

Kinlaw, Al. “Spilogale putorius”. Mammalian Species, no. 511, Oct. 1995, pp. 1-7. https://academic.oup.com/mspecies/article-pdf/doi/10.2307/0.511.1/8071380/511-1.pdf, https://doi.org/10.2307/0.511.1. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Wade-Smith, Julia, and B. J. Verts. “Mephitis mephitis”. Mammalian Species, vol. 173, 1982, pp. 1-7. ↩︎

-

GBIF. Occurrence Download. 2024. https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.vkb9te. ↩︎ ↩︎

-

USGS, U.S. Geological Survey. Annual National Land Cover Database. 2024. https://doi.org/10.5066/P94UXNTS. ↩︎

-

Tosa, Marie I., Damon B. Lesmeister, and Taal Levi. “Barred Owl Predation of Western Spotted Skunks”. Northwestern Naturalist, vol. 103, no. 3, 2022, pp. 250-56. https://doi.org/10.1898/1051-1733-103.3.250. ↩︎

-

Lesmeister, Damon B., Rachel S. Crowhurst, Joshua J. Millspaugh, and Matthew E. Gompper. “Landscape Ecology of Eastern Spotted Skunks in Habitats Restored for Red-Cockaded Woodpeckers”. Restoration Ecology, vol. 21, no. 2, 2013, pp. 267-75. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1526-100X.2012.00880.x, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-100X.2012.00880.x. ↩︎

-

Harris, Stephen N., Jennifer L. Froehly, Stephen L. Glass, Christina L. Hannon, Erin L. Hewett Ragheb, Terry J. Doonan, and David S. Jachowski. “High density and survival of a native small carnivore, the Florida spotted skunk (Spilogale putorius ambarvalis), in south-central Florida”. Journal of Mammalogy, vol. 102, no. 3, Apr. 2021, pp. 743-56. https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article-pdf/102/3/743/38820308/gyab039.pdf,https://doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyab039. ↩︎

-

Hern´andez-S´anchez, Alejandro, Antonio Santos-Moreno, and Gabriela P´erez-Irineo. “The Mephitidae in the Americas: A review of the current state of knowledge and future research priorities”. Mammalian Biology, vol. 102, no. 2, Apr. 2022, pp. 307-20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42991-022-00249-z. ↩︎